The Viking Age did not begin for a single reason, but from a convergence of economic, demographic, and political forces. Limited arable land and a growing population pushed many northerners to seek opportunity beyond the sea. Advances in shipbuilding provided a technical advantage — fast vessels made it possible to trade and to strike unexpectedly. Over time, commerce, violence, and migration became intertwined in a single system, in which merchants and warriors arrived first, and colonies and new centers of power followed.

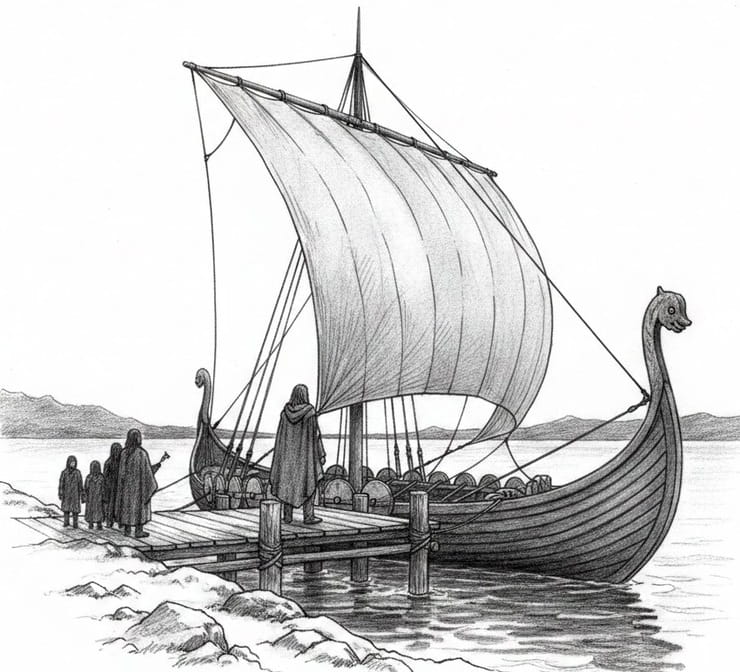

Dawn had not yet fully colored the sky when the ship was already waiting at the landing place. The water lay dark and still, touched only by a faint ripple against the hull, as if testing whether the vessel was ready for the journey. On shore, no one spoke. At moments like this, words felt unnecessary. A woman rested her hand on a child’s shoulder, and the child watched not his father, but the sail as it was slowly raised along the mast.

The man tightened his belt. At his waist hung a purse of silver — the remnants of earlier trade — and a knife sharpened the night before. He might return with furs, amber, and new connections. He might return with wealth taken by force. Or he might not return at all.

Behind him lay his home — smoke rising through the opening in the roof, a field still waiting to be ploughed, land divided among brothers. Before him stretched a road without tracks: water leading toward unfamiliar shores.

The sail filled with wind. The ropes drew tight. The choice had been made — between home and the road, between what was familiar and what was possible.

And there were more such people in Scandinavia than is often assumed.

Who Was a Viking, Really?

The word viking did not describe a people in the strict sense. It was a role — temporary and flexible. A man could be a farmer for most of the year, and then go to sea as a trader or a warrior. For this reason, when speaking about the causes of the Viking Age, it is important to understand that we are not dealing with a single type of person, but with several interconnected roles.

The first of these was the trader. Northerners were deeply involved in the exchange of furs, walrus ivory, amber, iron, and other goods sought after across Europe and beyond. Trade brought silver and luxury items, strengthened connections between regions, and opened new routes. Wealth was not born only in battle, but also at the market.

The second role was that of the warrior. Violence was not an end in itself, but it became a tool. Fast ships and the element of surprise made it possible to take in a single raid what might otherwise have required years of negotiation and payment. In a world where borders were weakly defended and coastal towns lacked fleets, military force became a means of accelerated enrichment.

The third role was the colonist. Where trading posts or temporary camps appeared at first, permanent settlements often followed. Land, whether taken by force or granted by agreement, became a new home. In this way, a Viking could turn from outsider into neighbor — and eventually into a local ruler.

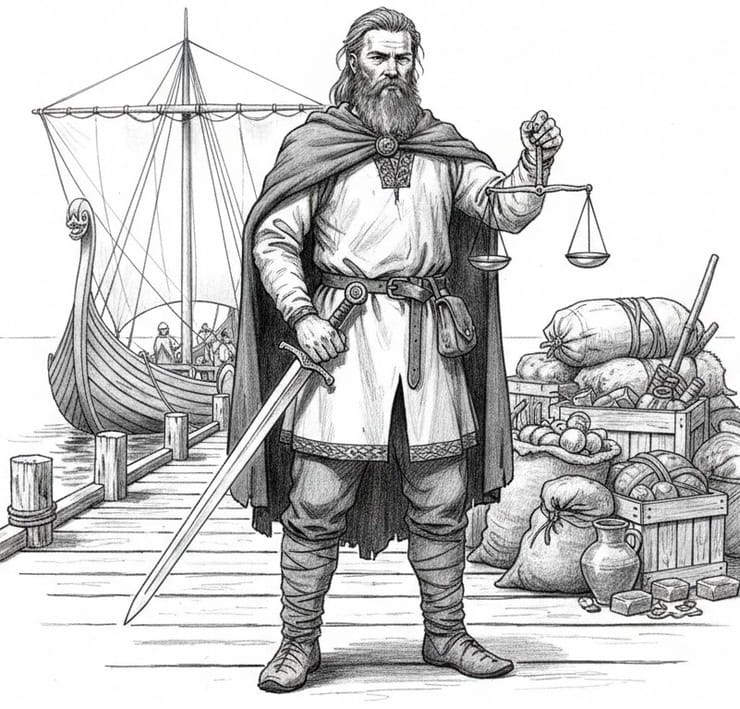

Imagine a trader at a landing place, holding folding scales in his hand as he weighs silver, a sword hanging at his belt. If an agreement is reached, he is a merchant. If not, he is ready to become a warrior. And if the land proves fertile and defensible, he may return not as a visitor, but as an owner.

But to understand why this role became widespread, one must first see what opportunities the North itself provided.

The Wealth of the North

When Vikings are mentioned, the imagination often turns to chests of gold carried out of monasteries. Yet northern wealth was not limited to the spoils of raids. A significant share of it came through trade — systematic, long-distance, and carefully organized.

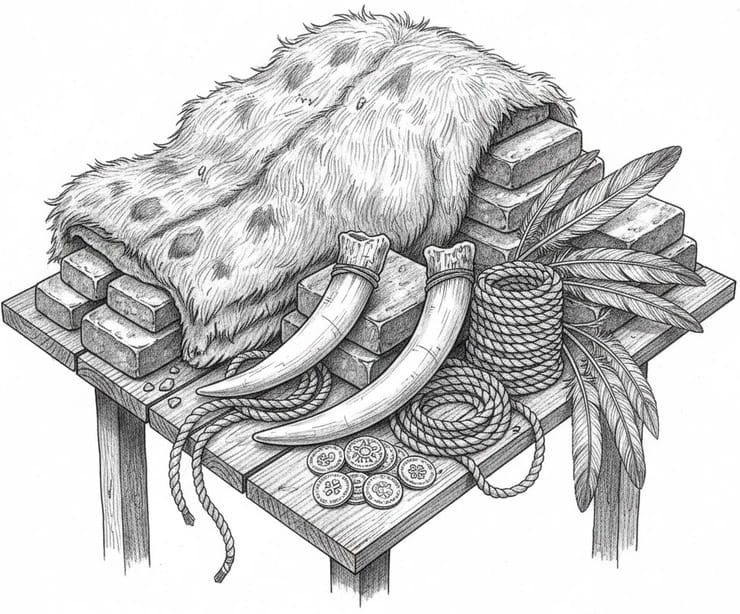

Scandinavia supplied Europe with what it lacked. Furs from northern animals were prized for their warmth and rarity; walrus tusks were used for carving and ornament; feathers and down filled cushions and garments for the elite; strong ropes made from northern fibers were essential for seafaring. Iron, mined and worked in the North, also found eager buyers. Together, these goods formed the basis of exchange, bringing silver, textiles, wine, and luxury items from the south.

Southern lands paid for northern goods not out of generosity, but necessity. Materials from cold regions could not easily be replaced by local resources. Demand for rare products — whether fur or walrus ivory — sustained stable trading relationships. For this reason, northern ships more often entered harbors as traders than as raiders, even though the two roles were never entirely separate.

How this trade functioned in practice, and what was considered true wealth in the North, can be seen through the story of one man — Ottar of Hålogaland, who left us a rare account of a world where wealth was measured not only in silver, but in herds, land, and tribute from neighboring peoples.

The Trader Who Revealed the Viking Economy

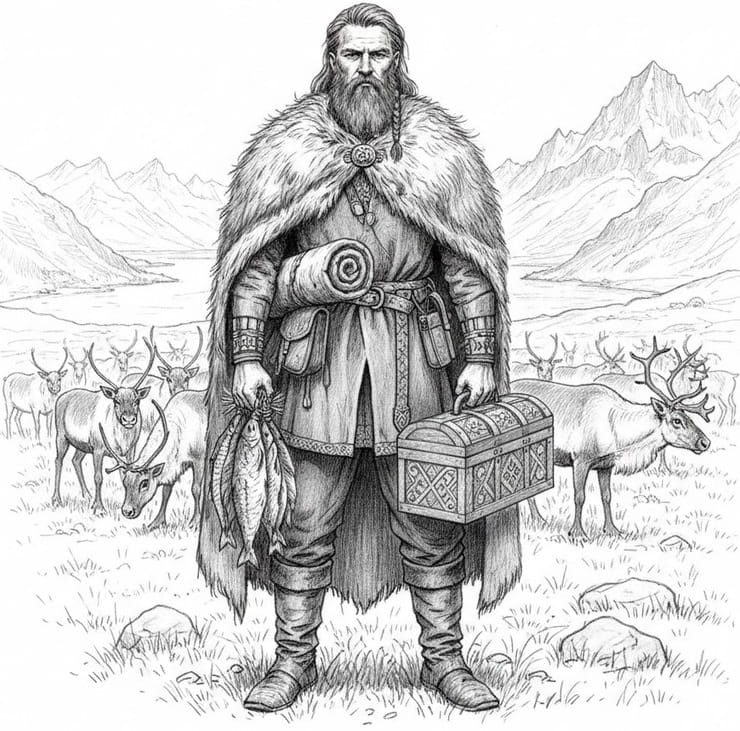

One of the very few people from the Viking Age whose own words have reached us was Ottar of Hålogaland, a northern region of Norway lying far beyond the familiar trading centers. His account was recorded at the court of the Anglo-Saxon king Alfred, and it remains a rare testimony to how northerners grew wealthy and how their trade functioned.

Ottar did not describe himself as a warrior or a conqueror. He emphasized that he was a prosperous man, but his wealth was not measured in silver alone. He owned herds of reindeer and received tribute from the Sámi. This tribute included valuable goods: furs, walrus tusks, feathers, and pelts of rare animals. It was precisely such materials that were in demand in the more southerly parts of Europe.

With these goods, Ottar traveled south to the major trading center of Hedeby (Heiðabýr). There, exchange took place. Northern resources were converted into silver, textiles, metal goods, and other luxury items. This was not an isolated transaction, but part of a stable system. People like Ottar connected the remote regions of the North with the markets of Europe, creating networks of exchange that generated profit without the constant use of violence.

Ottar’s story allows us to see the economy of the Viking Age from within. It shows which goods were valued, how wealth was accumulated, and why the sea became not only a road for raids, but an artery of trade. Through the life of a single individual, it becomes clear that the Viking Age was not only an age of the sword, but also an age of scales and counting.

But northern trade did not end in the west or the south. Other routes existed — longer, more dangerous, and often more profitable.

The Eastern Route

If the western routes led to Britain and Francia, the eastern route opened the way to the riches of Eastern Europe and beyond — to Byzantium, the imperial capital the northerners called Miklagarðr, “the Great City.” This path was no less important than the western seas, but it was far more dangerous.

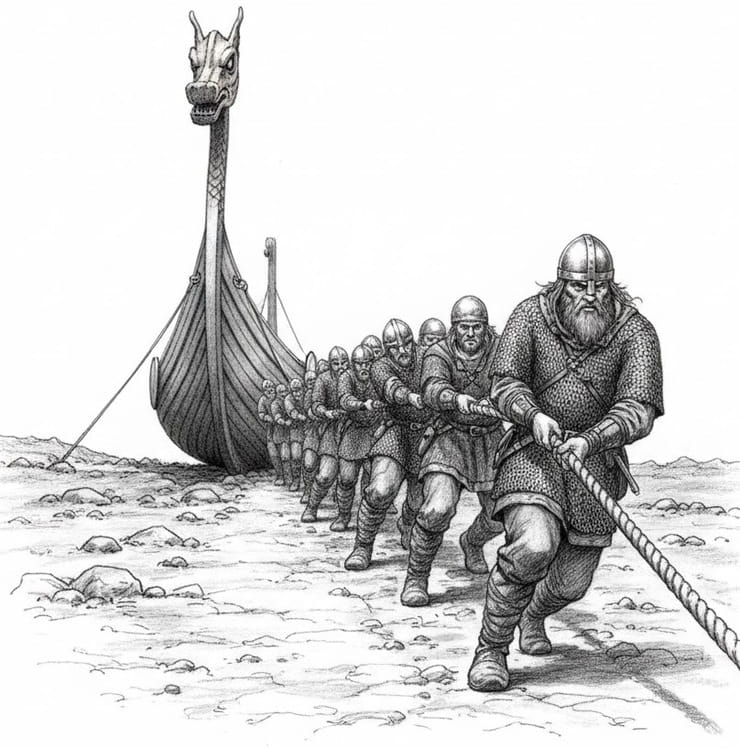

The journey began in the Baltic Sea and continued along the great rivers — the Neva and Volkhov, or the Western Dvina — before reaching a complex system of portages leading toward the Dnieper. In several places, ships had to be hauled out of the water and dragged across land, over rapids and through marshy ground. The Byzantine emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus, in his detailed writings, described the Dnieper rapids and warned of their dangers: violent currents, hidden rocks, and the constant need for protection against steppe raiders.

Men pull the ship across wet earth, ropes biting into their shoulders. Water roars behind them, chains clatter against wood. On a rise above the river, a lookout scans the open steppe — riders can appear faster than the ship can be lowered back into the water.

This route demanded not only strength, but organization. Convoys of ships traveled together for protection. Traders negotiated with local rulers, formed temporary alliances, or paid for safe passage. In return, eastern trade brought immense wealth: silver Arabic dirhams, silks, and luxury goods that would eventually find their way north.

And there was another commodity, often spoken of more quietly than the rest — slaves.

Captives taken in raids or wars became part of the trading flows. Slave trading was embedded in the economy of the eastern route and was one of the reasons expeditions deep into the continent continued for decades. The eastern path was a road not only to wealth, but to constant danger — a place where trade, violence, and risk existed side by side.

The Dark Side of Trade

The economy of the Viking Age was built not only on furs, iron, and walrus ivory. Embedded within it was another, heavier element — the trade in human beings. Both written sources and archaeological evidence increasingly reveal that captives became part of exchange in much the same way as silver or goods.

In major trading centers such as Hedeby, routes from the north, west, and east converged. Here, all kinds of commodities were bought and sold — and among them were people taken during raids or wars. Captives became laborers on farms, household servants, skilled workers, or were moved further along the trading routes toward other markets.

War, piracy, and trade did not exist as separate spheres in this world. A raid could yield silver, while captives provided an additional source of income. A trading expedition could turn into armed conflict if negotiations failed. The boundary between merchant and warrior remained thin and fluid.

From an economic perspective, this reduced risk. An expedition that failed to acquire sufficient silver or goods could still prove profitable through the sale of captives. This made overseas ventures more attractive and lowered the stakes for participants: failure in one form of gain could be offset by another.

Thus, silver and people became part of a single system of exchange. This was the reality of the age — complex, harsh, and contradictory — where wealth and violence often moved together.

Yet trade alone does not explain everything. There were moments when northerners chose not the scales, but the sword.

Why the Vikings Attacked

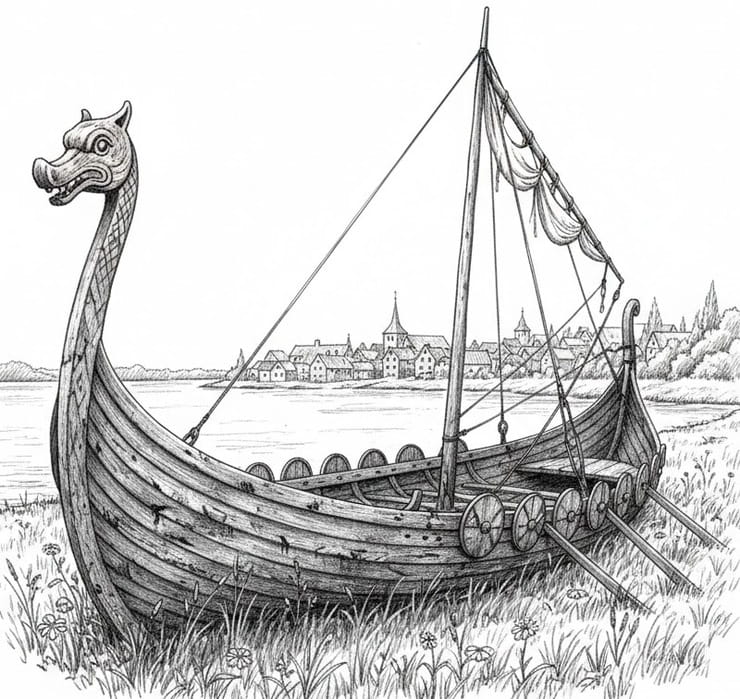

The reasons for Viking raids were not only economic — they were technical. The northerners possessed an instrument that gave them a decisive advantage: the ship, capable of appearing where it was least expected and vanishing before a response could be organized.

The shallow draft of their longships allowed them to approach almost any shoreline. A vessel could enter a river mouth, land on a sandbank, or be hauled ashore by its crew. Where heavier enemy ships could not follow, Viking crews moved freely upriver, reaching towns that believed themselves secure.

The combination of sail and oars made them largely independent of the wind. When the breeze failed or shifted, the ship continued under oar power. This meant that Viking crews could choose the moment of attack — and the moment of retreat — without relying on weather. Speed and maneuverability turned the sea into an ally.

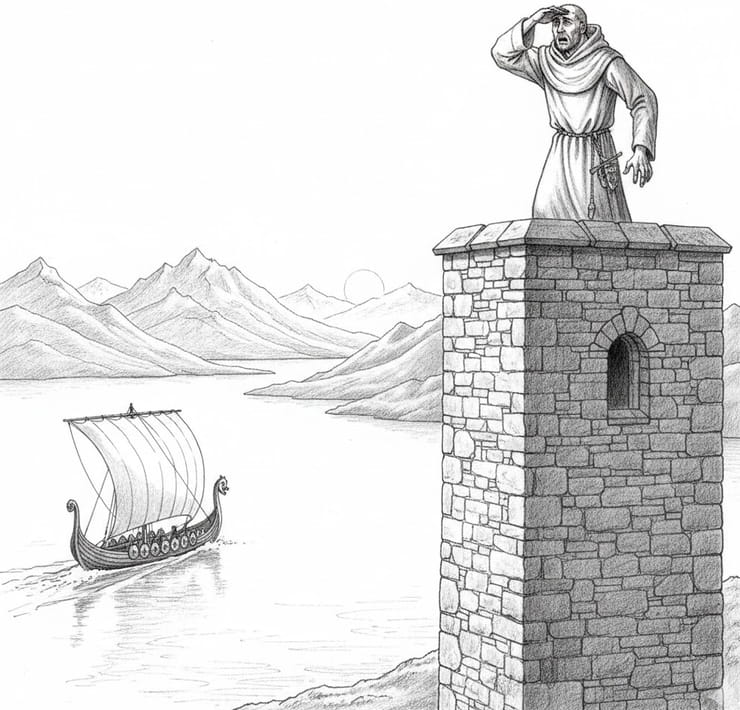

At the same time, European armies mobilized slowly. Coastal monasteries and towns rarely had effective seaward defenses, and permanent naval forces were uncommon. While messengers raced inland along roads, longships were already slipping beyond the horizon or disappearing into river channels.

A lookout on a monastery tower spots a sail at dawn. At first, he assumes it is a trader. Then he recognizes the long hull, the carved head at the prow. He understands — there is almost no time.

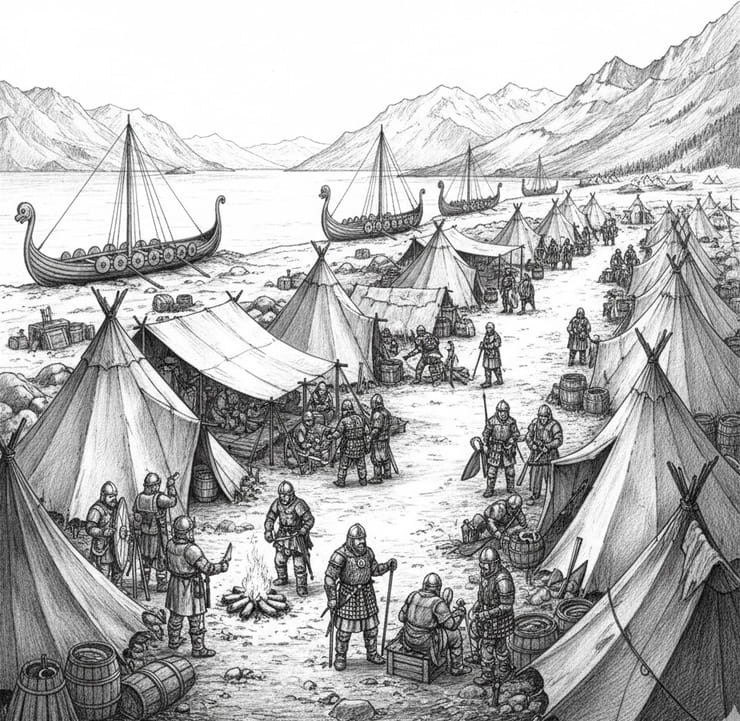

In later decades, the northerners began to use islands and river mouths as winter bases. These camps were nearly untouchable: water served as their defense, while proximity to trade routes allowed expeditions to resume quickly in spring. In this way, technology, geography, and calculation merged into strategy — and raiding became not a series of random attacks, but part of a coherent system.

Politics and Land

Economics explains much, but not everything. Behind overseas expeditions stood internal pressures as well — struggles for power, limits of available land, and the desire to secure one’s position in a rapidly changing world. The motivations of the northerners differed from region to region.

In Norway, the shortage of arable land was felt especially sharply. Narrow valleys and fjords could not be endlessly divided between generations. The consolidation of royal authority under Harald Fairhair became an additional factor: part of the aristocracy and many free farmers chose to leave rather than submit to the new order. For them, the sea became not only a route to trade or plunder, but a path toward new settlements in Iceland, across the islands of the North Atlantic, and beyond.

In Sweden, the focus shifted eastward. Here, trading posts and river routes linking the Baltic to the interior of Eastern Europe played a central role. Colonies and fortified stations along the eastern routes were part of a commercial strategy. They ensured control over waterways, protected trading caravans, and secured access to silver and other valuable goods.

Denmark occupied a different position. With broader fertile plains and a strategic location between two seas, the Danes could combine trade with territorial expansion. From here came many of the large expeditions to England, where raiding gradually gave way to conquest and the division of land.

Thus, some northerners sought markets above all else, others new shores on which to settle, and still others political power. These differences shaped the further development of the age — the rise of colonies, fortified camps, and trading centers that we will examine in later chapters. And at a certain point, expeditions ceased to be seasonal.

The Great Army: From Raids to Conquest

The early decades of the Viking Age were dominated by swift raids. Ships appeared without warning, took what they could, and vanished. Over time, however, the scale changed. Small warbands gave way to large, coordinated forces that no longer acted as temporary raiders, but as organized armies.

Anglo-Saxon sources of the ninth century refer to the so-called Great Army — a coalition of Scandinavian forces that arrived not for a single season of plunder, but with the intention of staying. This marked a fundamental shift. Instead of brief strikes, there was sustained presence; instead of temporary camps, the division of land and the establishment of control.

From this process emerged the region known as the Danelaw, where Danish laws and customs took hold. Here, warriors gradually became landholders. The sword gave way to the plough, the ship to a house and a field. What began as a military expedition ended in the creation of a new society, where Scandinavian and local traditions intertwined.

Similar developments unfolded in Frankia. Raids along the rivers Seine and Loire first brought loot, then agreements, and eventually land. Some northerners received territories in exchange for military service or the obligation to defend the region against further incursions.

In this way, raids evolved into conquest, and conquest into settlement. The scale of operations expanded, objectives shifted, and the Viking Age entered a new phase — one in which the pursuit of plunder increasingly gave way to the struggle for land and power.

How Conquerors Became Locals

One of the clearest examples of how Vikings transformed from raiders into rulers is the story of Rollo. In the early tenth century, he was granted land in Frankia in exchange for defending the coast against further attacks. This agreement marked a turning point. A former war leader became a duke, and his followers became landholders.

Thus emerged Normandy — the land of the “Northmen.” Yet holding power required more than guarding borders. It meant becoming part of an existing system. Numerically, the Scandinavians were a minority among the local population. Marriages with Frankish families, the adoption of Christianity, and the use of the local language gradually reshaped their identity. Within a few generations, the descendants of warriors spoke French and participated in the politics of Western Europe not as outsiders, but as part of it.

Assimilation was almost inevitable. To rule meant to administer, negotiate, and form alliances — all of which required speaking the language of one’s subjects and understanding their customs. Scandinavian traditions did not vanish overnight, but they slowly dissolved into the surrounding culture.

Only traces remained: certain place names, family names, faint echoes of an earlier presence. Sometimes it was the name of a village or a hill that became the last reminder that ships with carved heads once landed there.

Imagine a child in Normandy being sent to learn the “language of his ancestors.” Yet that language already sounds unfamiliar — spoken by elders, not by children. In this way, conquerors gradually became locals, and the Viking Age shifted into a new form of existence.

The story of Rollo was not an exception. It was a sign of broader change.

Why the Viking Age Ended

The Viking Age did not end in a single year, nor did it conclude with one decisive battle. It slowly dissolved into the changing political and cultural landscape of Europe. The same forces that had made overseas expansion possible — trade, migration, and conquest — gradually began to bind the Scandinavians to the lands they had reached.

The adoption of Christianity was a key part of this transformation. For Scandinavian rulers, the new faith was not only a religious choice, but a means of integration into the wider European system of alliances, dynastic marriages, and diplomacy. Christianity facilitated negotiation, strengthened political legitimacy, and connected northern kingdoms to the continent through shared institutions and norms.

At the same time, the meaning of the word “Viking” itself changed. Where it had once described a person who went on a sea expedition, that role gradually lost its central importance. Stable kingdoms, fortified towns, and developed trade networks demanded continuity rather than endless raids. Maritime expeditions did not disappear entirely, but they ceased to define everyday life.

Thus, the age did not end in defeat — it transformed. Temporary camps became towns, warbands became kingdoms, and scattered routes turned into established trade networks. In this new world, the word Viking slowly gave way to other identities — subject, merchant, ruler.

History continued, but in a different form.

Frequently Asked Questions about the Causes of the Viking Age

Why did the Viking Age begin?

The Viking Age emerged from a combination of factors: population growth, land shortages in certain regions, the consolidation of royal power, and advances in shipbuilding. Fast and maneuverable ships gave Scandinavians a technical advantage, while expanding trade networks opened opportunities for wealth beyond Scandinavia.

Was trade or raiding more important?

Both were closely connected. Trade provided steady income and long-term contacts, while raids offered a faster way to acquire silver and goods. Many expeditions combined both purposes. The balance often depended on local conditions and the level of resistance encountered.

What did Vikings sell, and what did they receive in return?

Scandinavians exported furs, walrus ivory, iron, amber, ropes, and other northern resources. In exchange, they obtained silver, textiles, jewelry, weapons, and luxury goods from Europe and the East.

Why were Vikings able to evade pursuit so easily?

Viking ships had a shallow draft and could enter rivers and shallow bays. The combination of sail and oars made them less dependent on wind. At the same time, European armies mobilized slowly, and permanent naval forces were rare.

What was the “Great Army,” and how did it differ from ordinary raids?

The “Great Army” refers to a large coalition of Scandinavian forces active in England during the ninth century. Unlike short-term raids, it aimed to settle, divide land, and establish lasting control over territory.

Why did Norwegians colonize Iceland and Greenland?

Land scarcity, political changes in Norway, and the desire for independence drove colonization. New territories offered the chance to own land and start anew, rather than remain subject to stronger rulers at home.

What was Frankia?

Frankia was an early medieval realm covering much of modern-day France and parts of Germany, formed after the fall of the Roman Empire. It was with Frankish rulers that Scandinavian leaders negotiated agreements, receiving land in exchange for service or protection.

Who were the Sámi?

The Sámi are an Indigenous people of northern Scandinavia and the Kola Peninsula, inhabiting areas that today lie within Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia. During the Viking Age, they practiced reindeer herding, hunting, and trade, and maintained contacts with Scandinavians. In some regions, Norse leaders collected tribute from Sámi communities in the form of furs and other valuable goods, which played an important role in northern trade networks.

How did Normandy emerge?

Normandy developed after an agreement between a Frankish king and the Viking leader Rollo. Scandinavian settlers received coastal lands and gradually became part of the local society, leaving behind only limited traces of their northern origins.

Why did Vikings assimilate?

Scandinavians were often a numerical minority among local populations. To maintain power and stability, they intermarried, adopted Christianity, and shifted to local languages. Over time, their distinct identity as “Vikings” faded within new political and cultural structures.

Can the Viking Age be seen only as an age of violence?

No. While raiding was highly visible, trade, colonization, and cultural exchange were equally important. The Viking Age was a period of intense interaction that reshaped Europe and the North Atlantic world.