The Vikings became the greatest sailors of the Middle Ages through a rare combination of factors: distinctive ships, refined navigational skills, and the geography of Scandinavia itself, which forced people to master the sea from an early age. Their light and swift vessels could cross open oceans, slip into shallow rivers, and undertake long expeditions ranging from Britain to North America. By observing the sun, stars, winds, and seabirds, they were able to hold their course even far from land, making the northerners the most experienced seafarers of their time.

A cold morning slowly rose over the fjord. The water lay almost still, broken only by faint ripples spreading from an oar as an old fisherman pushed his boat away from the stones. Along the shore, the sound of wood striking wood could already be heard — people were preparing a ship for departure. The tarred planks gleamed darkly in the grey light, the sail still lay furled, yet everyone present knew that within an hour the wind would fill it, and the narrow vessel would vanish among the islands, heading toward lands that lay beyond the horizon.

For the people of Scandinavia, the sea was never an obstacle. It was a road — the fastest, the most reliable, and often the only one. Forests blocked overland routes, mountains broke valleys apart, but water connected settlements, communities, and distant regions. A child born by the shore learned to handle an oar as naturally as a plough, and by adulthood could sense the coming of a storm long before the first heavy clouds gathered in the sky.

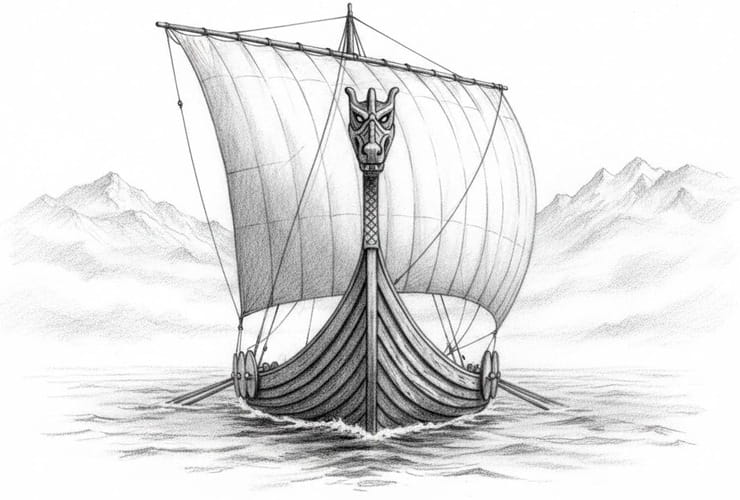

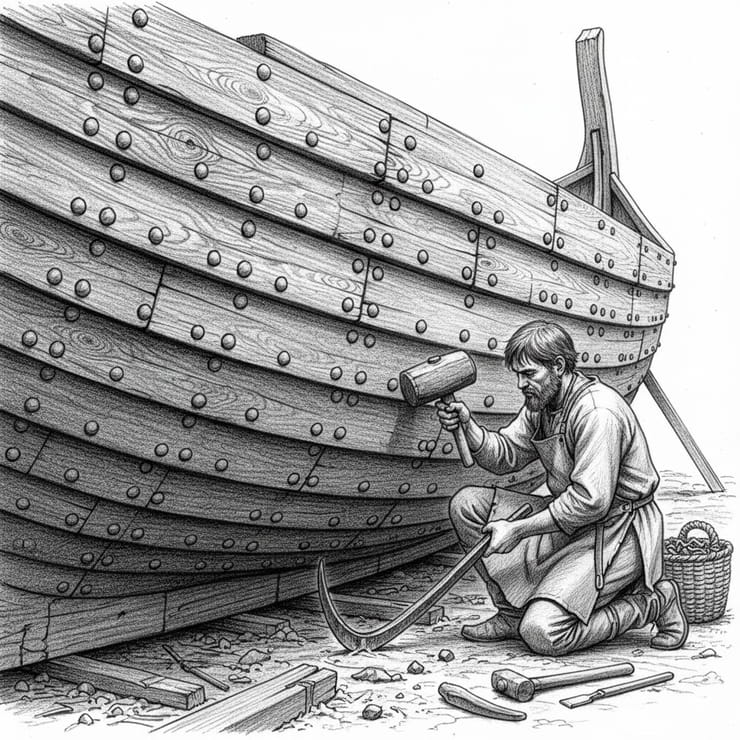

In time, the northerners learned not merely to venture onto the sea, but to master it. Their ships grew longer, lighter, and faster than those of southern peoples, and shipwrights guarded their knowledge as closely as warriors guarded the secrets of combat. Flexible hulls capable of enduring the удар of waves, shallow draughts that allowed entry into river mouths, and large sails that carried vessels across cold seas made possible what had once seemed unthinkable — voyages hundreds and even thousands of miles from home.

And when elongated silhouettes with carved animal heads on their prows emerged from the mist, the inhabitants of the coasts of Britain, Francia, or Ireland understood what they were seeing. These were people of the sea — people for whom distance was measured not in roads, but in winds, and whose story began where the line of the horizon came to an end.

Why Scandinavia Turned People into Seafarers

The land of Scandinavia itself seemed to push its inhabitants toward the sea. Long mountain ranges cut through Norway, dense forests covered vast parts of Sweden, and Denmark broke apart into hundreds of islands separated by narrow straits. Where roads and caravan routes crossed much of Europe, the North offered rocks, marshes, and impassable woodland. Travel by land was slow, difficult, and often more dangerous than venturing onto open water.

The fjords played a particularly decisive role. These deep sea inlets reached far into the interior, turning the coastline into a natural network of routes. The sea connected settlements more quickly than any overland path ever could. A person could set out by boat from their own shore and reach another region in a matter of days, without crossing mountains or forests. Over time, this way of life shaped habits and expectations. The boat became an extension of the household, and the sea a familiar space where people felt no less confident than on land.

Equally important was the shortage of fertile soil. Narrow strips of arable land along the fjords and scattered lowlands were not enough to sustain a growing population. Young men who inherited no land had little choice but to seek their fortunes elsewhere — through trade, service, or journeys to distant shores. A ship offered a way to leave home and return with silver, weapons, fine cloth, or even new land for settlement. Economic necessity slowly turned into outward expansion.

Over time, the people of the North came to see the sea differently from many of their neighbours. For much of continental Europe, the sea remained a dangerous boundary beyond which lay the unknown. For Scandinavians, it became a road — wide, open, and full of opportunity. It allowed them to move faster than by land, bypass mountains, enter river mouths, and reach towns that were beyond the reach of overland armies. This understanding — the sea not as a barrier, but as a pathway — became one of the key forces that shaped the northern peoples into a seafaring society.

But for the sea to become a road, the northerners first had to build ships capable of enduring its harsh nature.

In the evening, when the wind died down and the fjord grew dark, young men gathered by the landing place to listen to the stories of their elders. Some spoke of rich lands across the sea; others of storms that swallowed ships without a trace. Yet almost everyone knew that sooner or later he, too, would have to go to sea — because the land could not feed them all.

Ships That Changed the History of Europe

The strength of the Vikings lay not only in the courage of their warriors, but in ships unlike any other in early medieval Europe. Northern shipwrights built their vessels using clinker construction: hull planks were laid overlapping one another, each board covering the next and fastened with iron rivets. This method produced ships that were both light and strong. Unlike the heavy vessels of southern seas, northern ships could endure the удар of waves without breaking, flexing instead — almost like living beings adapting to the movement of the water.

It was this flexibility of the hull that gave them a decisive advantage in the harsh waters of the North Atlantic. When storms raised towering waves, the heavy ships of other peoples risked cracked planking, while the longships of the North bent and yielded, yet held together. Their shallow draught allowed them not only to sail the open sea, but also to enter narrow river mouths, be hauled onto shore, and launched again by the strength of their crews alone.

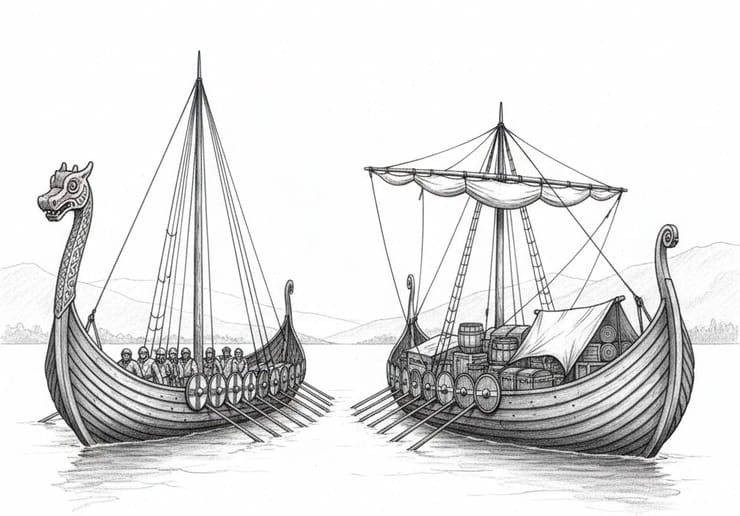

Several main types of such vessels existed. Warships — the longships — were long, narrow, and exceptionally fast. They were not designed to carry heavy cargo, but they could appear suddenly along a coastline, land warriors, and vanish just as swiftly. Trading vessels — knarrs — were broader and deeper, built to bear the weight of goods, livestock, and provisions for long voyages. Slower, but highly seaworthy, they were capable of crossing vast stretches of ocean, reaching Iceland, Greenland, and lands even farther away.

These characteristics made Viking ships nearly impossible for their enemies to intercept. They were faster than most European vessels, could travel under sail or oar, were not dependent on favourable winds, and could escape into shallow rivers where heavier pursuers could not follow. While coastal garrisons gathered to defend their towns, the longships were already disappearing beyond a headland or slipping upriver, carrying their spoils with them and leaving behind only smoke, ruins, and anxious rumours of people who had come from the sea.

Yet even the fastest ship was useless if its crew could not find a way across the open ocean, where there were no roads and no markers.

When a vessel left the shore and the last cliffs faded from view, a moment of silence would fall. The warriors stopped their joking, and the helmsman studied the sky, as if checking whether the familiar order of winds and stars had shifted. From that moment on, the fate of the ship no longer depended on strength of arms, but on the ability to hold a course where there were neither roads nor coasts.

How the Vikings Navigated the Open Ocean

For Viking-age seafarers, the most dangerous enemy was not a hostile weapon, but the vast emptiness of the ocean itself. Losing one’s bearing could mean drifting among the waves for weeks, until water and provisions ran out. For this reason, the art of navigation was valued no less than skill with the sword, and an experienced helmsman was often held in greater respect than the bravest warrior.

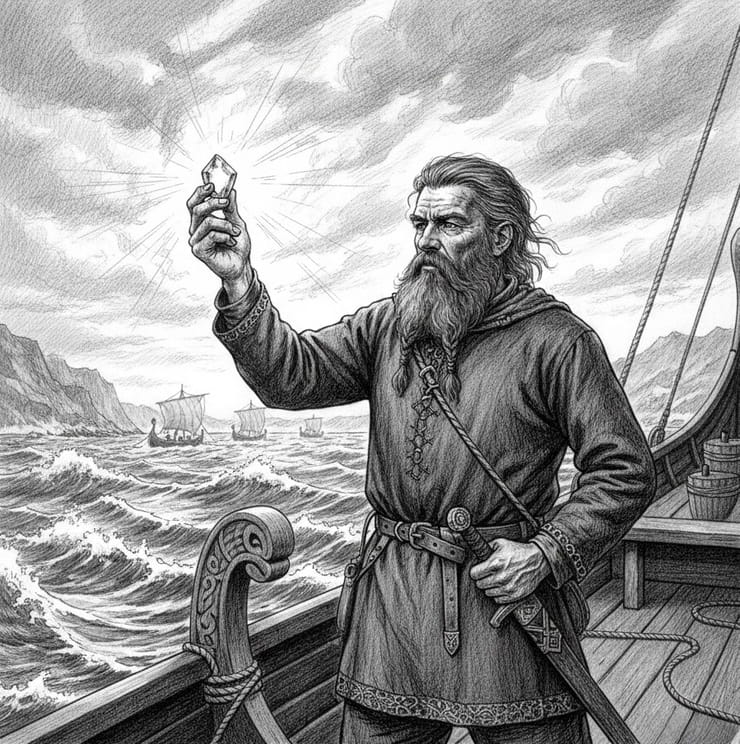

One of the most enigmatic tools mentioned in the sagas is the so-called sunstone. Modern scholars suggest that this name may have referred to Iceland spar — a transparent crystal capable of polarizing light. Even when the sky was covered by clouds, such a stone could help determine the position of the sun through patterns of scattered light, allowing sailors to estimate the cardinal directions. Although direct archaeological evidence for the use of such an instrument is scarce, the idea itself reveals how closely the northerners observed natural phenomena and learned to apply them at sea.

Navigation, however, was never limited to instruments alone. Sailors watched the world around them with care. The appearance of seabirds often signaled the proximity of land, since many species rarely strayed far from their nesting grounds. The behavior of whales and seals could hint at migration routes leading toward particular regions of the ocean. Even the color of the water served as a guide: lighter shades often indicated shallows or nearby coasts, while dark, almost black waters suggested great depth.

Over time, such observations solidified into established sea routes linking northern Europe with new lands to the west. One of the best-known paths ran from the coasts of Norway to Iceland, then on to Greenland, and farther still — to the lands the sagas called Vinland. These crossings demanded not only sturdy ships, but a precise understanding of winds, currents, and seasonal changes in weather. Generations of seafarers passed down knowledge of when it was safest to sail, where fog was most common, and which stars could be trusted to hold a course through the night.

Through this combination of careful observation, accumulated experience, and simple yet effective tools, the northerners managed to cross immense stretches of ocean long before the magnetic compass entered European navigation. They discovered new islands and traced routes that later peoples would follow.

Mastering the art of navigation gave the northerners more than the ability to keep their course at sea — it allowed them to establish reliable connections between distant lands. In time, these passages became regular maritime routes, known to every seasoned helmsman.

Days at sea stretched endlessly. At first, the crew counted the miles already sailed, then the remaining barrels of water. After weeks, they counted only sunrises, hoping that one of them would bring the cries of seabirds and the long-awaited scent of land.

Viking Sea Routes

Over time, the northerners turned the northern seas into a branching network of routes, known to experienced helmsmen as well as merchants knew the roads between towns. These routes did not exist on maps in the familiar sense. They were passed down orally from one generation to the next — knowledge of where favorable winds were most reliable, where hidden reefs lay beneath the surface, and which islands offered the best places to replenish fresh water.

One of the busiest directions led from the coasts of Norway and Denmark to the British Isles. The crossing was relatively short and allowed ships to reach wealthy monasteries, trading towns, and coastal settlements with speed. It was along this route that many Europeans first saw the longships of the North, appearing at dawn and vanishing just as suddenly as they had arrived.

Another vital route ran eastward — across the Baltic Sea and into the river systems of Eastern Europe. From there began long river roads that carried ships deep into the continent, reaching Slavic lands, major trading centers, and even distant Constantinople. In certain places, vessels had to be hauled ashore and dragged overland from one river to another, but it was precisely these portages that opened access to the vast markets of the eastern world, where the northerners traded in furs, amber, and silver.

The boldest routes lay to the west, across the cold waters of the North Atlantic. From Norway, ships sailed to Iceland — an island that became a crucial stepping stone for further journeys. From there, experienced seafarers ventured on to the harsh coasts of Greenland, and farther still, to the lands the sagas called Vinland. These voyages demanded not only strong ships, but precise knowledge of winds, currents, and seasons, for a single navigational error could lead to long and perilous wandering among ocean storms.

In this way, the northerners gradually created their own maritime map of the world — not drawn on parchment, but carried in the memory of helmsmen and passed on by word of mouth. It was this web of sea roads that allowed them, within a single generation, to transform from coastal peoples into travelers, traders, and warriors whose ships could be encountered from the rivers of Eastern Europe to the distant shores of North America.

Each of these routes meant weeks and months of arduous travel, during which the fate of a ship depended not only on winds and currents, but on the endurance of the people aboard.

Life Aboard the Crew

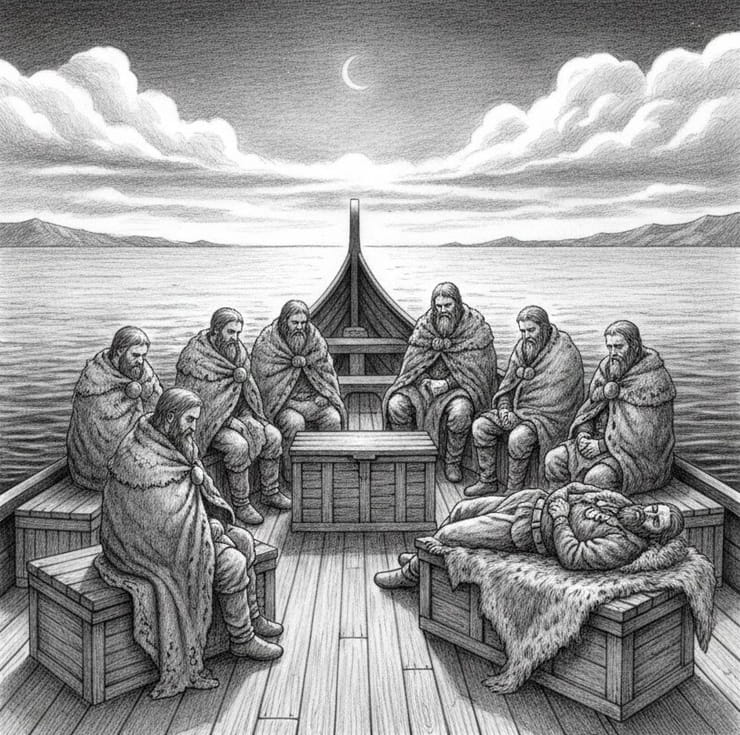

Life aboard a Viking ship rarely resembled the heroic scenes later celebrated in the sagas. Most of the time, seafarers endured cold, dampness, and constant exhaustion. The ships were open, without permanent decks or cabins, and people lived among weapons, water casks, and sacks of provisions, sheltering themselves only with woolen cloaks or stretched pieces of cloth.

Sailors slept where they rowed. Each man had a personal chest that served at once as a seat and as storage for his belongings. On cold nights, men often lay two to a hide to preserve warmth, and during heavy storms sleep was reduced to brief moments of rest between watches, when constant attention had to be paid to the wind and the state of the sail.

Food was simple and monotonous, but suited to long voyages. Dried meat and fish formed the basis of the diet, along with grain flatbreads, cheese, and sometimes butter. Barrels of sour milk or beer were common, as they kept longer than fresh water. On distant crossings, water was rationed with particular care and replenished whenever possible at river mouths or on islands. Any delay along the route could mean hunger, and the distribution of supplies was therefore tightly controlled.

Rowing demanded endurance, and the crew was divided into shifts. When the wind was weak or speed was required, one part of the crew worked the oars while the other rested, prepared for the next watch, or repaired rigging. On long passages, this system allowed the ship to keep moving for many hours at a time, though the constant physical strain quickly wore people down.

Illness posed no less a threat than storms. Cold, damp conditions and a limited diet led to fevers, inflammation, and exhaustion, while wounds received in battle or during work aboard the ship often became infected due to the lack of clean water and medicine. Experienced seafarers tried to carry simple remedies — herbs, salves, and bandages — but in serious cases, survival depended largely on the strength of the body itself.

Only strict discipline made order possible under such conditions. On board, everyone knew his role — who tended the sail, who handled the steering oar, who oversaw the distribution of provisions. Carelessness or disobedience could cost the entire crew their lives, and orders were followed quickly and without argument, especially during storms or combat. It was this combination of endurance, familiarity with hardship, and clear organization that made the crews of northern ships such dangerous opponents and enabled them to undertake journeys that seemed impossible to others.

It was these people — hardened by cold, hunger, and long crossings — who made what would later be called the Viking Age possible.

And yet, despite the cold, disease, and relentless labor, each spring the ships were launched again. People returned home thinner, but with silver, news, and stories of distant lands — and those stories were enough to gather new crews by the following summer.

Why the Sea Created the Viking Age

The sea gave the northerners their greatest advantage — mobility. While land armies moved for weeks along roads and mountain passes, ships could cover vast distances in a matter of days, appearing along coasts that were believed to be safe. Settlements, monasteries, and trading towns across Europe were prepared for threats from land, but attacks from the water often caught them unawares.

For this reason, the most powerful weapon of the Vikings was surprise. Narrow and swift ships allowed them to arrive suddenly at dawn, land warriors, and disappear just as quickly before local rulers could gather their forces. Even when pursuit began, longships escaped into shallow river mouths or vanished among islands and skerries where heavier vessels could not follow. In time, the mere report of northern ships was enough to spread alarm along the coasts of the North Sea and the Atlantic.

Yet the sea was not only a road for raids. The same ships were used for trade, and many voyages did not begin as military expeditions at all. The northerners carried furs, iron, amber, enslaved people, and crafted goods, returning with silver, fine textiles, wine, and luxury items from the south. Trade and raiding often overlapped: where defenses were strong, deals were made; where towns lay unprotected, wealth was taken by force.

Gradually, this maritime activity turned the Scandinavians into one of the most mobile peoples of their age. They founded settlements in Iceland and Greenland, served as mercenaries in Byzantium, traded along the rivers of Eastern Europe, and at the same time kept the coastal regions of Britain and Francia in constant anxiety. All of this was made possible by the sea — the road that connected distant lands faster than any overland route. It is for this reason that the Viking Age was born not on battlefields, but on the waves of the northern seas.

Yet the success of the northerners cannot be explained by skill and ships alone. Equally important was the fact that the lands they approached were largely unprepared for such a threat.

First came a ship. Then a trading post appeared, followed by a fortified camp. Years later, a new town rose on the shore. This was how the northern advance across the world began — quietly, with the sound of an oar striking water, long before the chronicles of Europe would speak of a “Viking invasion.”

Why Europe Was Unprepared for the Vikings

When the first northern ships began to appear along the coasts of Britain and Francia, European states faced a threat for which almost no one was prepared. Most coastal regions were defended primarily against attacks from land. Cities built walls, fortresses guarded roads and river crossings, and monasteries or trading settlements often had little or no protection facing the sea. The coastline was seen as a natural boundary, not a frontline — and so longships were able to approach the shore with minimal resistance.

Even when news of an attack reached local rulers, responses were slow. Medieval armies were assembled from feudal contingents that required time to receive orders, gather men, and march to the threatened area. While messengers carried warnings and warriors prepared to move, northern ships were already leaving the coast, carrying away loot and captives. This mobility rendered traditional defensive systems ineffective: armies could guard cities and roads, but they could not protect thousands of kilometers of shoreline.

The situation was made worse by the absence of permanent naval forces in many parts of Europe. Maritime power was limited to merchant vessels or small coastal boats, ill-suited to pursuing the fast and maneuverable ships of the North. Even when fleets were assembled, they were often slower than Viking longships and unable to follow them into shallow river mouths, where the attackers could find refuge.

Only after decades of repeated raids did European rulers begin to fortify their coasts, build watchtowers, and create their own fleets. But in the early years of contact, the advantage lay entirely with the northerners. It was this lack of preparedness that allowed the Vikings to spread their influence so rapidly along the shores of the North Sea and the Atlantic.

Frequently Asked Questions About Viking Seafaring

Did the Vikings use compasses?

There is no reliable evidence that magnetic compasses were used during the early Viking Age. In Europe, compasses are not widely mentioned until the 13th century. The sagas, however, refer to a sunstone — a possible navigational aid that modern scholars associate with Iceland spar, a crystal that can polarize light and help locate the sun even under cloud cover. In practice, Viking navigation relied primarily on observations of the sun, stars, winds, currents, and natural signs.

How fast were Viking ships?

Warships could reach speeds of roughly 10–15 knots under favorable winds, and even higher over short distances. Thanks to the combination of sail and oars, they could maintain speed in weak winds, making them significantly faster than many European vessels of the period.

How did the Vikings find Iceland?

The route to Iceland was gradually established through repeated voyages and accumulated experience. Sailors steered by the sun and stars, watched wind patterns, observed seabirds and marine animals, and noted changes in water color. Over time, these routes became well known and were passed down as oral navigational knowledge.

How many people could a longship carry?

Ship sizes varied, but large warships could carry between 40 and 80 warriors, sometimes more. Each rower occupied his own position and was also a fighter, ready to disembark immediately upon reaching shore.

Why could Viking ships enter rivers?

Their shallow draught allowed them to pass through very shallow waters and even be hauled ashore by the crew. This made it possible to strike deep inland by following rivers far from the coast.

How long did a typical sea journey last?

The duration depended on distance and weather. A crossing from Norway to Iceland usually took one to two weeks, while coastal voyages along Europe could last only a few days.

Did Viking ships carry only warriors?

No. Trading vessels known as knarrs were designed to transport goods, livestock, and settlers. These ships were used for the colonization of Iceland, Greenland, and other lands.

How did crews protect themselves during storms?

In severe weather, the sail was taken down, the ship was turned to face the waves, and course was maintained with the steering oar. The flexible hull construction allowed the vessel to absorb heavy wave impacts without breaking.

Did Viking ships have cabins?

No. Most ships were open. The crew slept on deck, sheltering themselves with cloaks, hides, or temporary fabric coverings.

Why were European fleets slow to counter the Vikings?

The main reasons were the speed and maneuverability of northern ships. They could appear suddenly along the coast, land warriors, and escape back to sea or into rivers that heavier pursuing vessels could not follow.

What Came Next

But the sea was only the beginning. Where northern ships first appeared, temporary landing places soon followed, then fortified camps, and later permanent settlements and trading towns that grew into centers of power and exchange. In this way, the Viking world gradually took shape — a network of sea routes, colonies, and markets linking Scandinavia with Britain, Eastern Europe, and even distant lands across the Atlantic.

In the following chapters, we will explore why the Viking Age began, where the first settlements emerged, how major trading centers functioned, and how fortified camps allowed the northerners to maintain control over newly reached territories.