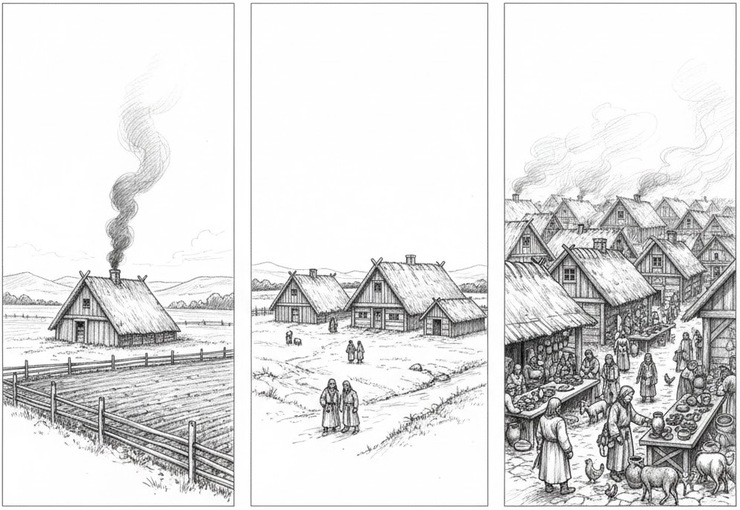

Vikings lived mainly in small rural communities and isolated farmsteads, set along the fjords, rivers, and fertile valleys of Scandinavia. Their homes — long wooden buildings with a hearth at the center — served both as living space and as the heart of the household economy. Harsh natural conditions and limited arable land meant that large towns emerged late. Early society relied on farming and self-sufficiency, and only with the growth of trade and maritime routes did permanent trading places appear, becoming the foundations of later Scandinavian towns.

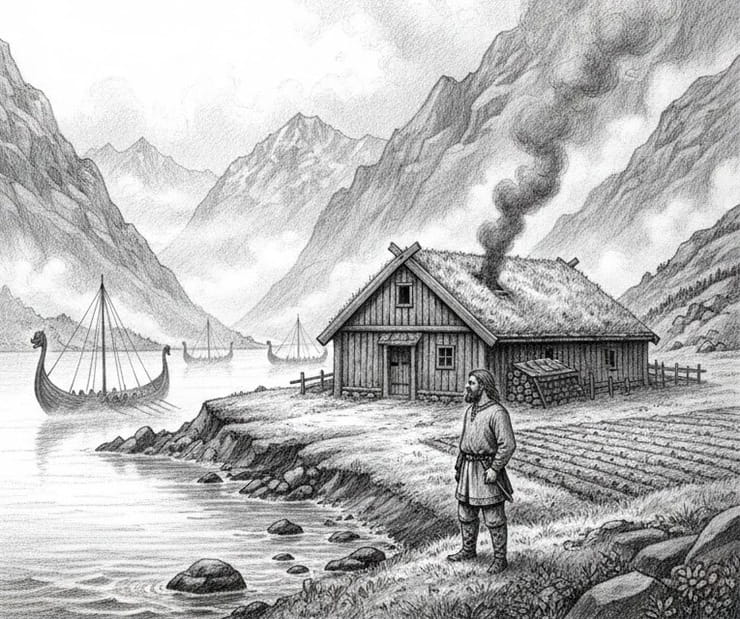

Mist drifted slowly across the water as the first rays of sunlight touched the roof of a longhouse. Smoke rose through the opening in the roof. The hearth was already burning, and the scent of damp wood mixed with the salty air of the fjord. Behind the house stretched a narrow strip of cultivated land, cleared of stones and roots. It was barely enough to feed a family through the long winter. Beyond it lay a forested slope, and beyond that — mountains, cold and silent.

A man stopped at the edge of the field and looked first at the land, then at the water. The soil gave bread, but demanded patience and labor. The sea lay calm, like a broad road leading toward places without stones or borders. Along that road, one could reach a neighboring settlement faster than through the forest — or sail farther still, to lands spoken of by those who had returned from the sea.

The smoke rose higher. The wind shifted. The day was beginning, and with it came the familiar choice — the plough or the oar.

The Land That Decided Everything

Viking settlement was never random. It closely followed the map of fertile ground and accessible routes. In a harsh climate with a short growing season, every cultivable valley mattered. Communities stretched along fjords and river valleys, where milder conditions, fresh water, fish, and narrow strips of arable land could be found. The fjord became more than an inlet — it was an axis of life. Along its shores lay farms, landing places, and small harbors that bound people together.

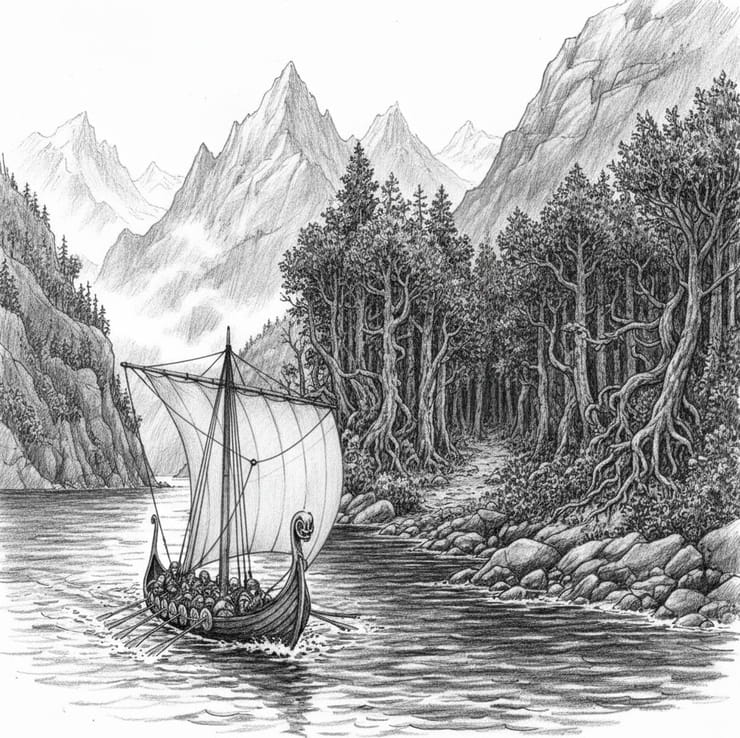

Mountains and dense forests, by contrast, divided communities. Norway’s high ranges, marshy lowlands, and the thick woodland of Sweden turned land into a barrier. Where a valley ended, isolation began. Travel overland was possible, but slow and exhausting; it was far easier to take a boat and follow the coast by water.

Sometimes the path leading away from a settlement narrowed and vanished among the trees, lost in damp moss and stone. But a boat, pushed from the shore, could continue. Along the water, toward the bend of a fjord where another valley opened — and with it, another narrow strip of land fit for life.

For this reason, many households existed in isolation. Farmsteads were placed on sunlit slopes, sheltered from the wind, where livestock could be kept and grain grown. Such homesteads might stand far apart, yet they were united by the sea — the only road not blocked by mountains or forests. It was the landscape itself that determined where a house could stand, where a community might endure, and where people would be forced to seek new land beyond the horizon.

Hundreds of such farms lined the northern coasts. Each depended on the same fragile balance: land, water, and a thin band of fertile soil.

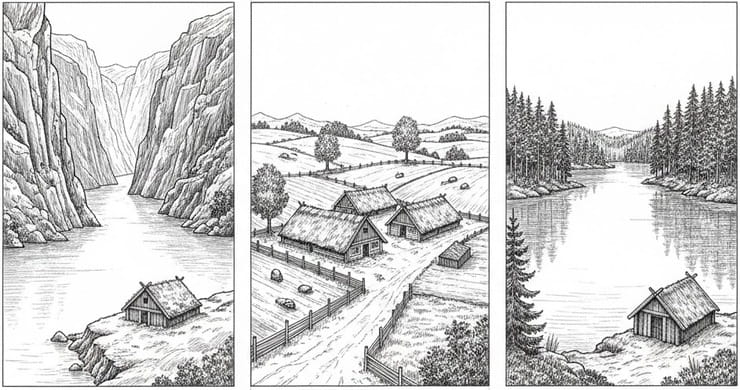

Three Scandinavias: Norway, Denmark, and Sweden Lived Different Lives

Although the northern lands were bound together by the sea, each part of Scandinavia developed according to its own logic, shaped by landscape and the amount of land fit for living. Geography determined not only where people settled, but also the direction of their movement — whether to remain at home or to seek new shores.

In Norway, life was especially bound to narrow valleys and fjords. Mountains covered most of the land, and arable ground existed only in thin strips along the water. As the population grew, pressure on resources increased: not every son could inherit land, and not every household could claim new fields. Here, more than anywhere else, the need to look beyond the horizon emerged early. Voyages into the Atlantic and the settlement of Iceland — and later Greenland — were not merely adventures, but practical solutions to the problem of limited land.

Where fields ended, the road to the sea began.

Denmark, by contrast, possessed a gentler landscape and far broader stretches of fertile plains. Here it was easier to expand cultivation, bring new land under the plough, and form a denser network of settlements. For a long time, population growth could be absorbed through internal development rather than large-scale emigration. Danish lands became a strong foundation for the rise of early trading centers, while their position between the Baltic and the North Sea enhanced the importance of maritime routes.

Sweden followed yet another pattern. Vast lakes and river valleys played a central role, with farms and communities clustering along their shores. Forests and interior distances separated regions from one another, creating strong local variations. The southern region of Skåne, for example, resembled the Danish model with its more developed agriculture, while central and northern areas oriented themselves toward lake and river routes that linked them to the Baltic world.

Thus emerged three versions of northern life: mountainous Norway, lowland Denmark, and lake-and-river Sweden. Each shaped the character of its people in different ways, determining whether expansion would take place at home or across the sea. Yet despite these differences, the foundation of life remained the same everywhere — not the harbor and not the market, but the house and the field.

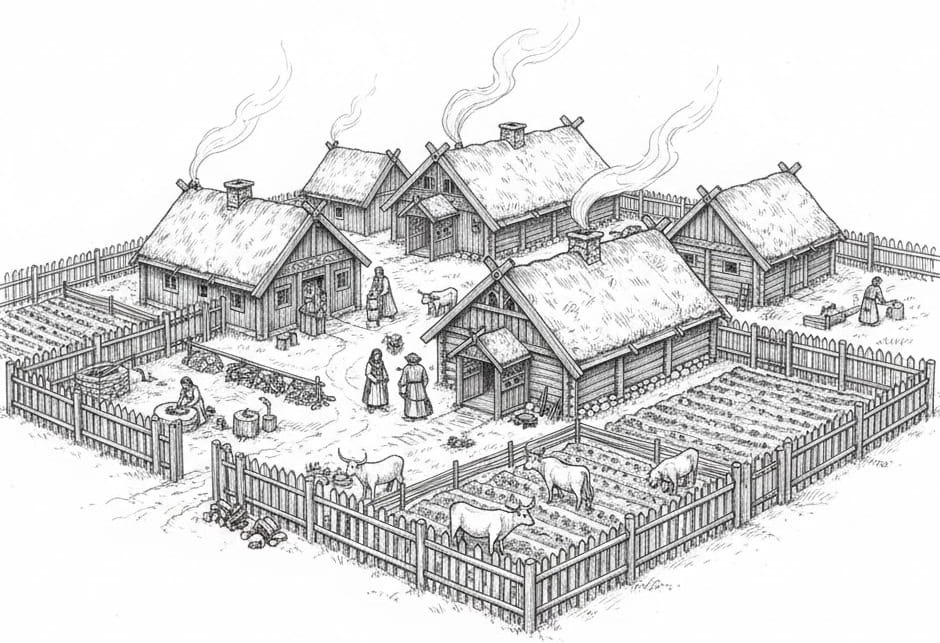

The Village

When we speak of Vikings, imagination often turns to busy harbors and markets. The reality of early Scandinavia was different. The foundation of society was the village — or even a single farmstead — standing on its own piece of land with a view of the water. Settlement took the form of a scattered network of households spread along valleys and fjords. At times, houses clustered more closely to form a small village, but more often each farm existed largely on its own, relying first and foremost on its own resources.

A typical homestead included a longhouse, outbuildings, fenced areas for livestock, and small fields. Families sought to provide for themselves: they grew grain, kept animals, gathered fish, and worked wood. Within a community, there was usually a minimal range of craftsmen — a smith able to repair tools and weapons, a carpenter, sometimes a potter or a worker in bone. Yet craft remained, in most cases, secondary to farming rather than the basis of an urban economy.

This is why true towns were slow to appear. A town requires constant exchange, a steady flow of goods and people, and a degree of specialization. In a society where nearly every household aimed to be self-sufficient, the need for a large center remained limited. As long as a farm could supply food, clothing, and tools, there was little pressure to create complex urban structures.

Gradually, however, the logic of life began to change. Sea routes connected distant regions, and with the ships came new goods, ideas, and opportunities for exchange. Self-sufficiency ceased to be the limit when new possibilities lay beyond the horizon.

How the First Towns Emerged

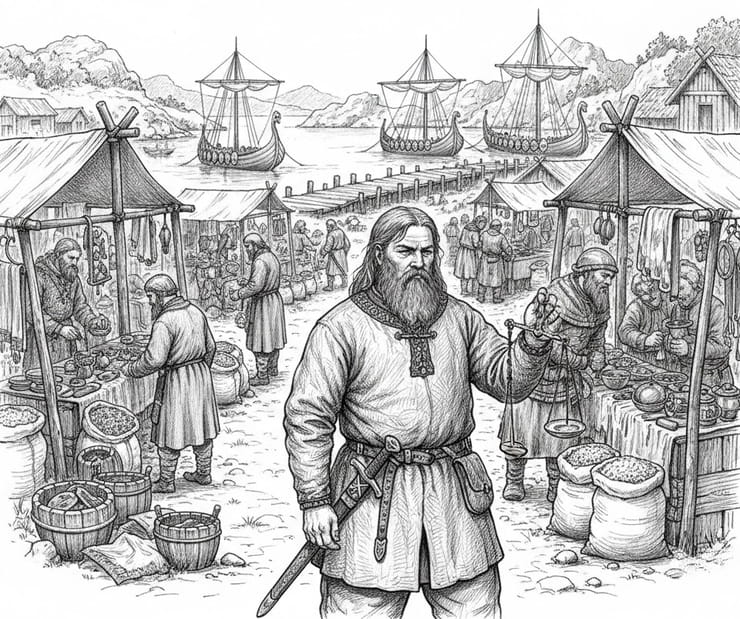

Around the late eighth and early ninth centuries, places began to appear in Scandinavia that could no longer be described simply as villages. These were trading sites — points where sea routes, overland paths, and the interests of people from different regions converged. Such settlements did not arise by chance. They required a sheltered harbor, space for large ships to moor, and room for people from surrounding farms to gather.

Contacts with West European and Frisian merchants played an important role. They brought not only goods, but the very idea of regular exchange: silver coinage, folding scales, standardized measures. Trade, once occasional, began to take on a permanent character.

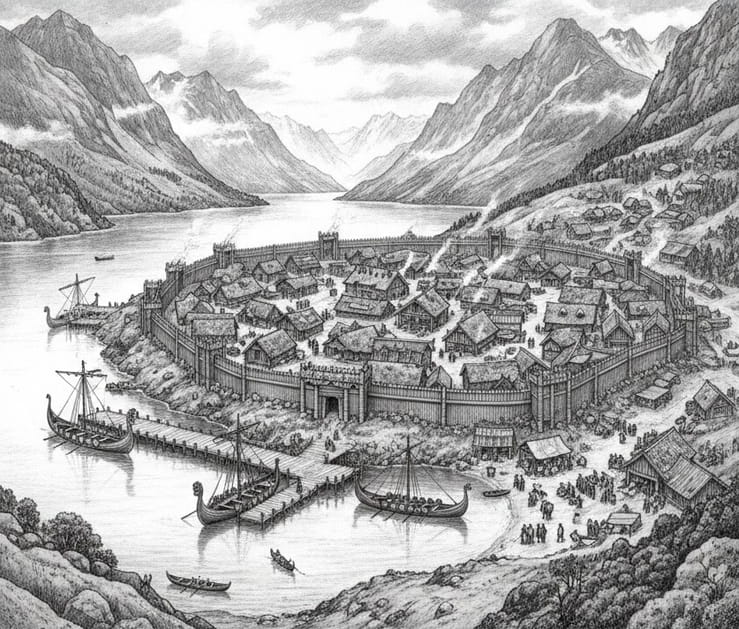

Location was decisive. A trading place had to be accessible by water — since the sea linked Scandinavia to the wider world — and at the same time connected to inland areas so that farmers could bring their produce. Many such centers lay deep within fjords or along lake shores, where they were easier to defend. A market meant a concentration of silver, weapons, textiles, and enslaved people — and therefore risk. Convenience of harbor went hand in hand with the ability to control approaches and, if necessary, organize defense.

On a warm day at the landing place, one could see a familiar figure: a man in a woolen cloak holding folding scales in one hand, a sword hanging at his belt. He weighed silver, inspected goods, argued over prices — and never stopped watching his surroundings. Trade brought wealth, but demanded caution. In these new places, one had to know how to count and how to defend oneself at the same time.

In this way, trading sites gradually became stable centers of attraction — the seeds of future towns. Here a new phase of Scandinavian society began, one in which farming was no longer the sole foundation of life, and exchange and maritime connections grew ever more important. Some of these places would, in time, become true hubs of the northern world.

Examples of Trading Centers

The earliest Scandinavian trading centers did not emerge on open coastlines. They were founded where geography itself offered protection and advantage — deep inside fjords, along lake shores, or at points where maritime and river routes intersected. These places became nodes in a growing network that connected Scandinavia to the wider world.

In Norway, such a center was Kaupang (Old Norse Kaupangr, English Kaupang), a trading site located deep within a sheltered bay. The very word kaupangr meant “market” or “place of trade,” reflecting its function. Its position allowed control of access from the sea while maintaining links with inland regions.

In Denmark, the most important node was Hedeby (Old Norse Heiðabýr, also known in the German tradition as Haithabu). Situated at a strategic point between the Baltic and the North Sea at the base of the Jutland Peninsula, it became a gateway for goods moving between continental Europe and the northern lands. Few places played a greater role in the long-distance trade of the Viking Age.

In Sweden, Birka (Old Norse Birk or Birca) and Helgö (Old Norse Helgøy, “holy island”) were of particular importance. Located on islands and along lake shores, they benefited from natural defenses and control over inland waterways. Their distance from the open sea was not a weakness but an advantage, providing security and the ability to regulate trade flows.

Such places quickly became magnets for craftsmen and merchants. Where people gathered regularly, demand arose for specialized skills: smiths, jewelers, and workers in bone and glass found steady work. Exchange turned into a system, and a system required organization. Trading sites gradually filled with workshops, storehouses, and dwellings, becoming stable centers of economic life.

Each of these centers had its own history, its own connections, and its own role within the wider network of northern routes. And each of these nodes of the northern world will be explored in a separate chapter.

Archaeology

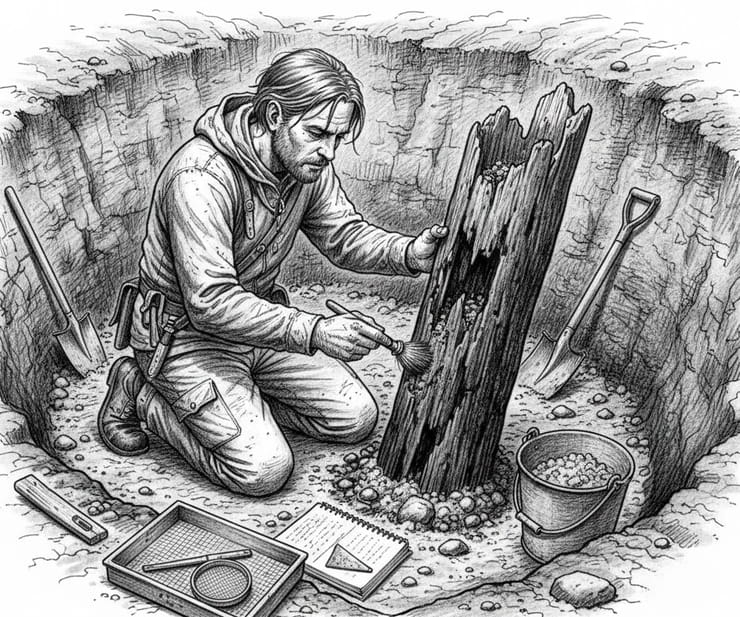

Viking settlements rarely survive as picturesque ruins. Wooden houses, earthen fences, and farm buildings decayed over time, and new farms, churches, and later towns rose in their place. Rural settlements were especially vulnerable to disappearance. Each generation built over the traces of the previous one, and the remains of early structures are often hidden beneath later construction or long-ploughed fields. The archaeologist must read the ground as carefully as a helmsman reads the sea.

Burials remain one of the most important sources of information. Burial mounds, stone settings, and graves with grave goods reveal social structure, levels of wealth, and even long-distance connections — through jewelry, weapons, and objects brought from distant lands. Runestones, raised in memory of the dead or the honored, add names and fragments of stories, linking material remains to individual lives.

Of particular value are hoards — hidden deposits of silver, coins, and ornaments. These are found in the ground, beneath house floors, or near ancient routes. Such discoveries show that parts of the population possessed considerable wealth, even when this is not always reflected in burial practices. Often, a person concealed their valuables in times of danger and never returned to reclaim them — and these forgotten caches become silent witnesses to the past.

Yet all sources have their limits. Rich graves of the elite are more visible and better preserved than the modest burials of ordinary people. Enslaved individuals and the poorest layers of society remain almost invisible in the archaeological record, buried without grave goods or in places that left little trace. For this reason, the picture of the past always demands caution: archaeology does not show society as a whole, but only those fragments that happened to survive a thousand years.

And still, it is through these fragments — the traces of houses, burial mounds, runic inscriptions, and buried silver — that we can reconstruct patterns of settlement and understand how a network of farms and trading sites gradually gave rise to a new northern world. But the land is not the only keeper of memory. Sometimes, history survives in words.

What Place Names Tell Us

Sometimes the past survives not in the ground, but in words. Place names form a hidden map of Viking settlement, preserved in language. Wooden houses have long since decayed, fields have been ploughed hundreds of times, yet the endings of names still point to where a new farm was founded, a village grew, or the frontier of settlement expanded.

Especially revealing are the elements -by, -torp, and -toft. The ending -by meant “village” or “settlement” and is often associated with Danish influence. In Denmark itself this appears in names such as Sønderby or Vesterby, while in England it survives in towns like Grimsby, Whitby, and Derby, where Scandinavian settlement during the Viking Age left a lasting mark. Each of these names speaks plainly: here stood a village founded or inhabited by Scandinavians.

The element -torp originally referred to a “new farmstead” or an offshoot of an older settlement. It appears in names such as Torp, Sandtorp, or Björketorp in Sweden and Norway. These toponyms point to expansion — moments when part of a family or a new generation moved away from the original homestead to establish its own holding.

The ending -toft is linked to the idea of a plot of land or enclosed homestead. In Denmark and the British Isles, names such as Lowestoft or Langtoft preserve this meaning. They refer not to an abstract village, but to a defined piece of land — a yard with a house, outbuildings, and fields, tied to a particular family or lineage.

This naming tradition spread far beyond Scandinavia. Eastern and northern England are dense with -by and -thorpe (the English form of -torp), reflecting Danish settlement in the period of the Danelaw. These names are evidence that the northerners did not arrive only with the sword, but also stayed with the plough. At times, a word proves more durable than stone.

One can imagine the moment when a man, having cleared a new patch of land, names it for himself or for the features around him — “the farm by the birch,” “the new holding,” “the village by the bay.” He gives the name without thinking that centuries later it will be printed on a map. Yet generation after generation passes, and his word outlives both him and his house.

In this way, language becomes a witness to history. If one looks closely at the map, it reveals not just geographic labels, but traces of human movement, settlement expansion, and the shaping of the northern world. From scattered farms, from trading sites, and from names carved into stone emerges a single picture — the world of the Vikings, soon to extend beyond Scandinavia.

Settlements as the Foundation of the Viking Age

First came a house, with smoke rising from its roof.

Then another house nearby.

And a generation later, the noise of a market.

The Viking Age did not begin with raids or distant expeditions, but with land — a narrow strip of cultivated soil by the water, where a longhouse stood and livestock grazed. The land fed the family, set the rhythm of life, and defined the limits of possibility. The sea, however, bound these scattered households into a single system, turning fjords and rivers into roads along which news, goods, and people moved.

Gradually, the self-sufficient farm ceased to be a closed world. Regular exchange, meetings with merchants, and the inflow of silver began to change the structure of society. Where once there had been only a house and a byre, a trading site appeared; around it grew workshops, storehouses, and permanent inhabitants. Over time, such places became towns — centers of craft, power, and wealth.

This process can be traced step by step: from isolated farm to village, from village to market, from market to town. And where wealth and importance accumulated, the need for protection soon followed — fortified camps and defensive structures became a new reality of the northern world.

Thus, settlements formed the foundation of the entire age. Without them, there would have been no trade routes, no overseas colonization, and no military expeditions. It is with them that the story of the northerners begins — and to them we will return when examining the causes of the Viking Age, the great trading centers, and the fortified camps that reshaped the map of Northern Europe.

Frequently Asked Questions about Viking Settlements

What did a typical Viking settlement look like?

Most settlements consisted of one or several farms located along a fjord, river, or fertile valley. The central building was a wooden longhouse with a hearth in the middle. Nearby stood outbuildings, livestock enclosures, and small fields. Each farm functioned as a largely self-sufficient unit, capable of supporting a family without constant reliance on external trade.

Why were there so few towns at the beginning of the Viking Age?

Early Scandinavian society was based on agriculture and local craft production. Most households provided for themselves. A town requires permanent exchange, specialization, and population concentration — conditions that emerged only with the growth of maritime trade in the late eighth and ninth centuries.

What do the endings -by, -torp, and -toft mean in place names?

The ending -by usually indicates a village or settlement and is often associated with Danish influence. -torp referred to a new farm or an offshoot of an existing settlement. -toft is linked to a plot of land or homestead. These elements help historians trace patterns of colonization and settlement expansion.

Why were trading centers built deep inside fjords or along lakes?

Such locations were easier to defend. Deep fjords and lake shores allowed control of access by water and reduced the risk of sudden attack. These sites were often positioned where maritime and overland routes intersected, making them ideal for trade.

What sources are most important for studying Viking settlement patterns?

Archaeological evidence is central: remains of buildings, burials, silver hoards, and runestones. These are complemented by the study of place names and by later written sources, which help provide broader context.

Why have so few traces of rural farms survived?

Wooden buildings decayed over time, and later generations often built on the same sites. Agricultural activity also disturbed or destroyed surface remains. As a result, archaeological evidence from farms is often fragmentary.

What can Viking Age hoards tell us?

Hoards are hidden deposits of silver, coins, and jewelry. They point to developed trade networks and the accumulation of wealth. In some cases, hoards suggest that parts of the population were more prosperous than burial evidence alone would indicate.

What are runestones, and why are so many found in Sweden?

Runestones are commemorative monuments with inscriptions, raised in memory of the dead or significant events. They are especially numerous in Sweden, where the tradition of erecting them was more widespread. Runestones help link archaeological finds to specific individuals and families.

Were Viking settlements fortified?

Most rural farms had no substantial fortifications. However, trading centers and strategic locations could be protected by earthworks, ditches, or natural barriers. In later periods, specialized fortified camps began to appear.

Did all Vikings live under similar conditions?

No. Living conditions varied greatly depending on region, land availability, and social status. People in the fertile plains of Denmark, the mountain valleys of Norway, and the lake districts of Sweden faced different opportunities and constraints, which shaped the character of their settlements.